Nicholas Knouf

Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

This essay examines a series of events that took place over a few days around the summer solstices in 2004 and 2005. These events, under the collective title of fadaiat—libertad de movimiento y libertad de concimiento (freedom of movement and freedom of knowledge) ‘took place’ within the Madiaq region of Spain and Morocco and the space of the Straits of Gibraltar in between. [1] This fixing of a temporality and a spatiality is indeed only provisional as fadaiat took ‘place’ prior to, after, within, and beyond the confines of a bounded series of days or a given physical location. The ambiguity of pinpointing final ‘locations’ in time and space of the fadaiat project reflects the ambiguity of its subject, namely the relationship of people and knowledge in border regions, with both imbricated among a digital world without ‘borders’. Borders are fixed as black lines on a map, electronic current flowing through the wires atop a separation wall, and in the lines before passport control agents. Yet borders are also malleable for the free flow of capital, and are thus forced to become partially permeable by the corresponding need for human labor to develop that capital. Fadaiat worked within these contradictions and thus became not only a reflection on these issues surrounding borders, not merely a conference of like-minded individuals, but rather a space for the development of responses and alternatives to the hardening of ‘Fortress Europe’ and its antagonism towards Muslim and/or African immigrants and refugees. The event brought together an amalgamation of collectives keen on reconfiguring social-technical assemblages. In the words of the fadaiat editorial team,

borders are habitable territories that can’t be reduced to lines on a map. They are environments that favour mixing and exchange, highly dynamic territories that generate a gradation of shared spaces, where the nature of passing through prevails over that of the barrier. To cross their thresholds means to physically move from one place to another, but, even more so, it implies the start of a transformation, to becoming-others (Monsell Prado and de Soto Suárez 2006: 169).

A consideration of borders is therefore not only a geo-political rumination, but also a rethinking of what it means to be amongst others. This is key given the marginalized history of the Ottoman Empire within Africa and the Iberian peninsula, the continued presence of Great Britain in Gibraltar, and the legacy of French, Italian, and Spanish holdings in north-western Africa, including the Moroccan-surrounded, yet territorially Spanish, free-trade exclaves of Ceuta and Melilla on the African continent.

The fadaiat project is vast, encompassing a book (with texts in Spanish, English, and Arabic), software, meetings, collectives, individuals, videos, and sound. Therefore this paper will be in two parts: the first laying out the project itself and describing one of its primary instigators, the Spanish collective hackitectura; and the second detailing a single aspect of the project, the creation and use of a non-commercial wireless link between Tarifa (in southern Spain) and Tangier (in northern Morocco). This transmission provided the first civil digital wireless data link between the two continents, enabling a series of events (including meetings, presentations, and parties) to take place amongst and between people who could not be co-present physically as a consequence of geographical and national borders. The second part will tie these actions to the earlier practice of pirate or free radio, and specifically to Félix Guattari’s support of Radio Alice in Bologna, Italy, in the late 1970s and participation in Radio Tomato in Paris, France, in the early 1980s. [2] Guattari, through his radio activities and his theorisation of subjectivity, provides a productive means of understanding the importance of events such as fadaiat insofar as they perform different expressions of individual and collective desire.

Hacking (physical, digital, social, individual) architectures

Fadaiat is the work of hackitectura (hackitectura.net 2011), a collective founded in Spain by Pablo de Soto, Sergio Moreno and José Pérez de Lama (also known as osfa). [3] Working since 1999, hackitectura has taken a special interest in creating alternative cartographies of physical and digital space, specifically areas that are overdetermined by state and corporate mediation. Their name, a portmanteau of hacktivism (which is itself a portmanteau of hacking and activism) and arquitectura, the Spanish word for architecture, is meant to suggest the productive possibilities of changing physical and digital space through the use of computational technologies. Hacktivism can be understood as a counter to the depoliticised ideology that is often assumed to underly the development of computer software and hardware, an ideology that presumes the neutrality of technology. Thus the hacktivist is concerned not only with questioning and responding to the means of technological production, and showing that its presumed neutrality is actually political, but also with deploying this critique by designing, developing, and implementing alternative uses of technology for activist purposes. [4] hackitectura takes this further by engaging hacktivism within spaces both physical and digital. Their work therefore considers the role of technology in controlling and mediating access to space and conceives of different uses of this technology to provide for spatial reconfigurations that generate new forms of individual and collective subjectivity. Pérez writes, ‘The concept of hackitecture itself proposes a practice which recombines physical spaces, electronic flows and social bodies, carried out by teams of architects, programmers-technologists and citizen-activists’ (Pérez de Lama 2009: 103). Besides fadaiat, hackitectura has produced a number of other projects including TCS2 Extremadura, Emerging geographies (2007), a geodesic dome near an abandoned nuclear power station that enabled local residents, including schoolchildren, to imagine alternative futures for the area; and Wiki-Plaza (2005), an attempt to provide a wiki-like construction of public space that was showcased in Seville and Paris.

hackitectura achieve their broadened concept of the word space by conflating the physical and the digital, seeing the two as fundamentally intertwined. In describing a series of hackitectura projects, Pérez notes that, ‘None of the spaces explained would have existed in the way they did without their digital extensions’ (Pérez de Lama 2009: 104). Physical space determines the limits of digital space (how far wireless signals can travel, digital firewalls that restrict the flow of bits from one nation to the other) while digital space places limits on mobility in physical space (the electronic checking of passports at borders, the impressions others have of us based on our digital activities). By failing to see how the two mutually effect and construct each other, we would fail to understand how power in one space can migrate to be power in the other space, and to show power is always already inextricably intertwined in the two spaces. hackitectura’s key move is to understand this mutability of power, and to suggest that by hacking the power relationships within one space we can potentially affect the power relationships in the other.

This negative dialectical construction of physical and digital power—necessary to the free-flow of capital and labor in contemporary neoliberal societies—additionally provides an opening for resistance, one that hackitectura exploits in part through the use and creation of libre (free) software. [5] For example, by creating the tools needed to easily distribute audio/visual streams using libre software, hackitectura and their colleagues remove the need for commercial tools that perform the same function, while also, and perhaps more importantly, providing a widely broadened space for people to become individual and collective broadcasters, thus breaking proprietary control of media distribution technologies. So, what could at first blush be seen as a merely technical activity—the writing of software to distribute audio and visual data—is, upon further reflection, a deeply political act meant to increase the ability of people to present themselves outside of corporate and state controlled representations. This move has to be understood within the contemporary moment, where the so-called ‘open’ nature of the Internet is rather controlled by a variety of state, corporate, and military actors with interests that are often antithetical, to say the least, to notions of social emancipation or collective desire. Bringing this desire into the physical space, at many hackitectura events DJs and VJs perform long into the night, often using the very libre software that provided the bases for the technical development of the projects. [6]

Coupled to this interest in providing alternative representational strategies in digital space, hackitectura also produces radical cartographies of physical space, especially as it concerns the abilities of people to freely move about the world. This mapping process requires much more than the understanding of geographical or territorial boundaries. Indeed, to see the concept of ‘freedom of movement’ alone one must map the social-technical assemblages of border control, the creation of ‘free trade zones’, the (forced or willing) transfer of ‘labor’ from one locale to another, the tendrils of the tourist industry, the fear of ‘invasion’ by the Other, the accounts of migrants attempting to cross the Straits, examples of resistance—and so on (Monsell Prado and de Soto Suárez 2006: 14–35). Simultaneously considering the physical and digital cartographies enables elucidation of each in the other, as diagramming the physical placement of network infrastructure (such as wireless access points or data centers) can provide clues as to the arrangement of the underlying digital networks.

The hackitectura ‘collective’ has to be seen within a wider array of social relations involving individuals, groups, organisations, ad-hoc arrangements, and so on. hackitectura is thus not only the name for a collective of researchers, but it also is a signifier for a group that belongs to a broader network of collectives and individuals, all of which were necessary for the fadaiat project. Indeed, the list of contributors (Harris and Gough 2004a) contains the names of ninety individuals and thirty-eight organisations who provided various types of expertise, the union of which made fadaiat possible. This is a form of affinity organisation well-known amongst alter-globalisation activists.

A special mention must be made, nevertheless, of the relationship with Indymedia Estrecho (Indymedia Estrecho/Madiaq 2011), as this link additionally ties fadaiat and hackitectura into a wider array of alter-globalisation activities. [7] The organisation of Indymedia Estrecho consists of individual Indymedia groups in southern Spain and across the Straits of Gibraltar into northern Morocco, an area collectively known as the Madiaq. Thus the link with Indymedia Estrecho was also part of the additional work to make connections not only with other Indymedia nodes in the Madiaq region, but also a wider collective of collectives that reaches across Europe, Africa, and other continents via transnational movements of autonomous orientations. Participation in fadaiat is not tied to a single geographic region, then, but rather is based on affinity and mediatised representations built by members of the Indymedia collectives themselves. The work needed to create these bottom-up representations requires a hybridity of actors and networks: actors, in the sense of the combination of disparate yet complimentary abilities into a collective project; and networks, in the both the re-appropriation of military and commercial technology and the (re-)activation of corporeal and non-computational experiences of networks. [8] Given that this region is heavily monitored and militarised—creating an antagonistic relationship with not only the present-day inhabitants, but also the history of movement between the two continents—the novel collectivity evinced here needs to be understood in an agonistic sense rather than simply antagonistic. This combination, across a heterogeneity of spaces and times, suggests ways that new types of relations can be formed through coming-together, the collective becoming of the socio-technical assemblage. For members of the fadaiat project this would create a different space, ‘an other territory that would connect the two shores of the Straits of Gibraltar—known as Madiaq in Morocco—through a hybridisation of atoms and bits’ (Monsell Prado and de Soto Suárez 2006: 171).

The fadaiat events

The fadaiat project was broad in its physical, digital, and human extents. It was a continuation of hackitectura’s earlier work in the Andalusian region of Spain, especially the multitude connected event of late 2003 that produced a telematic ‘space of flows’ amongst a series of internet-connected nodes throughout Europe and South America (de Soto Suárez 2005). Fadaiat included the two main gatherings, the production of new cartographies of the Madiaq region, programming work that resulted in libre software for the streaming of both audio and visual data, and solidarity actions with local support groups and NGOs that work with the immigrant and migrant population. The first edition in June of 2004 was titled fadaiat: transacciones, with the subtitle of ‘freedom of movement / freedom of knowledge’, and was focused primarily on setting up the wireless data link between the south of Spain and the north of Morocco, between the Castle of Guzman el Bueno in Tarifa and the University Abdelamlek Esaadi and a terrace next to the Cafe Hafa in Tangier (Pérez de Lama, de Soto Suárez and Moreno 2005). Describing the first event, one of the main organizers, Florian Schneider, wrote,

In the small chapel of the fortress squatters from Madrid discuss with Maroccon Indymedia activists and with socilogists [sic], that are researching the shift of the border towards the south. Local refugee supporters are exchanging with womens rights activists from Larache, with community representatives from the Rif-mountains, with spokespersons from the movement of the unemployed as well as with labour leaders from the greenhouse industries in Almeira. Radio and filmmakers are documenting, mixing, editing and sending their conference contributions in the internet. As soon as it gets dark outside, the DJ’s and VJ’s, musicians and performance artists take the command over the three inner wards.

The climax of the spectacle is a video conference via a wireless connection from Tarifa to Tanger, that was accomplished by the netactivists through an extra strong antenna. The small transmitting mast, that only got the official administrative permission the day before, is standing on the heighest [sic] of the four towers of the fortress and looks more like a fan. Long wires are meandering around the castle walls, run across the narrow stairways and historic castle rooms, in which the activists go into a huddle behind the screens (Schneider 2005).

The second edition in June 2005 was called fadaiat: borderline academy, and was more concerned with creating tactical cartographies of the straits (Monsell Prado and de Soto Suárez 2006: 229) and undertaking a ‘participatory workshop […] to design a “Strategic Plan for the Technological Observatory of the Straits”’ (172). [9] This mapping of and intervention within the Madiaq region was seen by the editorial team of fadaiat to be representative of wider global concerns regarding labor, migrancy, and geo-political configurations. ‘The Straits of Gibraltar is a laboratory-territory of the contemporary world. Multiple processes coexist and combine in such a way that Migrations and Work become key words for reading the transformations taking place.’ (169) Authors and presenters examined the discourse surrounding ‘Fortress Europe’ and the fear of invasion (Pullens 2006), questioned assumptions about borders and citizenship within contemporaneous neoliberal economies (Mezzadra 2006), considered specific issues of migrant labor within the region (Maleno 2006), and mapped the social axes of labor and production (Toret and Sguiglia 2006).

The wireless link is important not only for the symbology of a connection across the span of the Straits of Gibraltar, but also for linking this event with earlier work in pirate radio. The link itself, however, cannot be understood to immediately transform its surroundings. While much academic and journalistic discourse from the 1990s and into the early 2000s exalted the ‘inherently’ emancipatory power of network technologies such as the Internet and the mobile phone, an alternative set of work situated these developments within existing corporate, state, and military power structures. [10] Network technologies, in this latter view, most often reify the status quo, and the abilities and affordances of the technologies are governed not by an idealistic realm of cooperation, but rather the ideology of the market. The former position could be termed emancipatory technological determinism , meaning the belief that particular technologies, simply by virtue of their existence, will revolutionarily transform for the ‘better’ (often from the standpoint of a progressive politics) psychological and social structures. This viewpoint is profoundly ahistorical and atemporal, ignoring the role of ‘external’ factors in the development and spread of new technologies. [11] By contrast, the work of Felix Guattari enables us to compare the new network technologies with previous developments, such as video, Super 8 film, and cable access television, and the corresponding malaise regarding their inability to immediately effect change. We can address the ecology of technological apparatuses by understanding their complicated imbrication with psychological, social, and environmental processes (Guattari 2008).

Transmission across the Straits

The goal: setup a WiFi data link that could enable the sending of streaming video and audio across the Straits of Gibraltar. The places: Tarifa, Spain and Tangier, Morocco, separated by around 32 kilometers (19.9 miles) over water. This distance does not approach the current ‘records’ for long-distance wireless data sharing using standard WiFi technology; however, the Straits are a very noisy Hertzian space with interference from myriad military installations and commercial shipping routes. Additionally, the locations are known for fierce weather including high winds, making the stability of the installation vitally important. [12] The technical information about the wireless link (Harris and Gough 2004b) goes into great detail regarding the necessary calculations, the setup of the network, questions of regulatory permission, and lessons learned. (See Figure 1 for a collage of images from the fadaiat book that show some of the spaces and technology involved in the creation of the link.) Resolving these significant technical challenges was necessary in order to enable the creation of participatory and collaborative media representations. The data link provided the frame for the transmissions to take place; it was a necessary, but not sufficient, element in the collectively-produced events spanning the two continents.

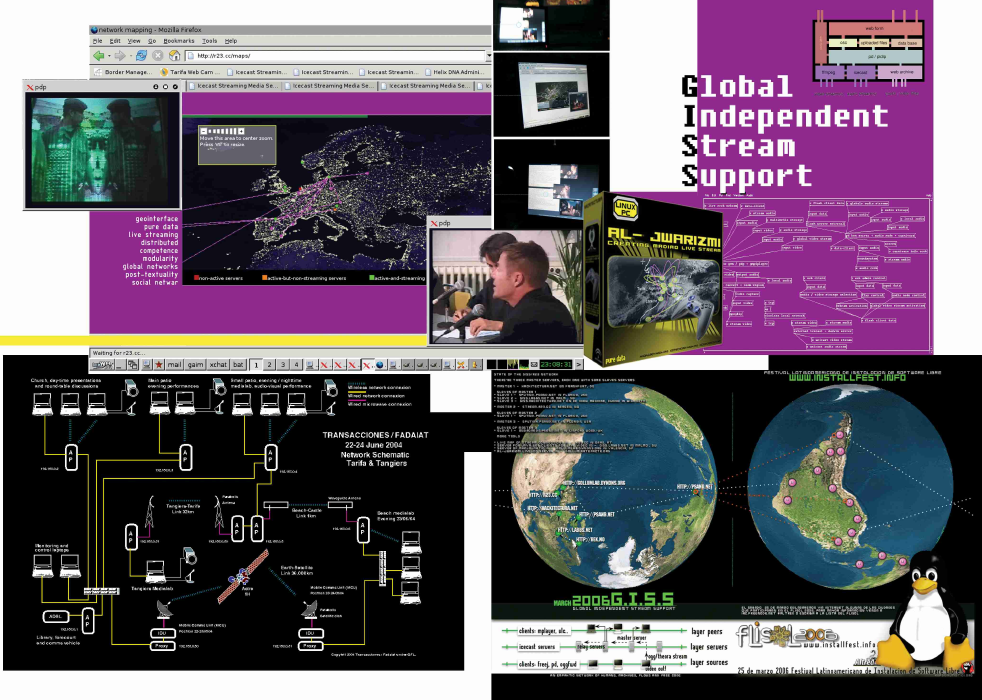

Coupled to the hardware data link was the need for a new type of software that enabled the easy creation of audio/visual streams. Termed Al-Jwarizmi (Al-Jwarizmi Contributors 2005)/GISS (Global Independent Stream Support) (GISS Contributors 2008), the software is partially built in Pure-Data (PD), an open platform for the real-time manipulation of data often used for live experimental media performances. (See Figure 2 for an image from the fadaiat book that shows some of the GISS interface and its relevance within the wider wireless data link network.) GISS allows the user to create a ‘channel’ via a web interface that anyone can then connect to in order to send or receive images and/or sound. As of writing there are a number of channels available that provide various types of ad-hoc Internet radio-style streams; these streams can be setup and taken down at will, providing a flexibility that is lacking in more stable types of media streaming services. In addition to fadaiat, GISS has been used to stream events such as the World and European Social Forums and concerts in support of the residents of Gaza. In the words of one of the developers of GISS, Yves Degoyon, the idea was to create a system to counter traditional media that ‘rarely speak of the real and daily life and problems of the common people’ and open a space to ‘create a human-scale media and an empathic network of human experiences in different locations of the globe’ (Degoyon 2007).

Collage image showing the two spaces in Tangier and Tarifa. In the upper-left images, note the dish that is the Tangier node of the link. In the lower left of the collage is a conceptual map of the data networks involved in the project, including those in other countries that provided server space or solidarity events during <em>fadaiat</em>. In Monsell Prado and de Soto Suárez 2006: 50–51 and licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical-ShareAlike Spain 2.5.

Collage image showing some of graphics relevant to the GISS component of the <em>fadaiat</em> project. In the lower left is the network diagram for the entire wireless data link. Note in the lower right image the reference to the upside-down map of South American by the Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres-García; this tactic of rotating or reflecting maps is used extensively within the <em>fadaiat</em> book as a way of destabilizing our views of cartography. In Monsell Prado and de Soto Suárez 2006: 46–47 and licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical-ShareAlike Spain 2.5.

Forfadaiat 2004, GISS enabled people to communicate via representations of their own making and via a non-commercial link setup by their own labor. GISS was the glue that enabled conversations, presentations, and a rave to take place across the Straits and beyond. The development and spread of GISS post-fadaiat speaks to a desire for communication tools that serve the needs of the community rather than commercial stakeholders. In contrast to closed commercial products such as Skype, GISS enables independent multi-way conferencing and media sharing, and so an alternative way of experiencing communications media. GISS does require a certain amount of technical knowledge to run; however, this knowledge is not proprietary and owned by a singular entity, but can instead be shared with others via channels such as GISS itself. Unlike a closed-source, black-box program like Skype whose inner workings are hidden from view, GISS rewards the effort needed to make it work, drawing the user into both a wider space of experimental media technologies as well as a community of people eager to share their knowledge.

Important for fadaiat and hackitectura is the understanding that GISS is not to be used in only an instrumental sense. It does not exist solely for the rational discussion of immigration in the context of the fadaiat events. In addition to this use, or alongside it, is the expression of collective desire through parties and raves. Indeed, imagery from the project (Monsell Prado and de Soto Suárez 2006: 42–45) links it to the rave culture of the 1990s, and especially the spontaneous expression of jouissance that was channelled through the Reclaim the Streets (RtS) movement. [13] RtS eschewed rational discourse that merely talked about alternative use of public space; rather, they performed their desire through the creation of mass parties in open spaces and roads throughout cities in Europe and North America. The linking of fadaiat to this history, and the use of GISS to create a telematic space of celebration, continues the embodied expression of desired alternatives.

Pirate radio and technological apparatuses

In his 1932 essay ‘The Radio as an Apparatus of Communication’ Bertolt Brecht wrote of his concerns about the development of radio, shortly before Joseph Goebbels’ well-known speech regarding radio as a tool of propaganda (Goebbels 1999). In Brecht’s view, ‘radio is one-sided when it should be two–. It is purely an apparatus for distribution, for mere sharing out’ (1964: 52). Radio was becoming a ‘substitute’ for other forms of media (such as theatre, concerts, and the opera) rather than a medium in and of itself, rather than an expressive space that utilised the unique properties of the technology. His suggestion was to call for a conceptual shift: to see the radio as a means of communication (in the two-way sense) rather than distribution (in the one-way sense). Since radio (by wireless transmission) can carry sound from one central location to a variety of peripheral locations, why could it not also carry the thoughts and affect of individuals and collectives to wider audiences? This would not be merely a ‘renovation’ (in Brecht’s words) of ideological apparatuses, but rather an ‘innovation’ that would be a radical rethinking of the relationships between people and the state, away from fascist paternalism and towards a more communist orientation. Brecht’s entreaty, while technologically ambitious, was not entirely outside the realm of possibility, and underpins the argument that technological development does not occur in the abstract, minus the influence of existing institutions, but is rather shaped and partially determined by present powers. [14]

So if radio did not renovate ideological apparatuses as Brecht desired, what about other mass media technologies of later decades, such as Super-8 film, video, or cable-access television? Félix Guattari asks this very question in his essay ‘Popular Free Radio’, suggesting that one of the reasons why these other technologies had not taken hold had to do with the mechanics of the technologies themselves: ‘with video and film, the technical initiative remains, essentially, the object of big industrial enterprise; with free radio, an important part of the technology depends on the improvisational ability of its promoters’ (Guattari 1996 [1979]: 73).[15] What Guattari is hinting at here is the ability, with radio, to build transmitting apparatuses with a minimum of parts, and to hide transmission antenna in a variety of inconspicuous locations. Additionally, broadcasting rigs can be moved rapidly and replaced quickly in the case of a raid by the state. Free radio becomes a nomadic technology, temporarily located within a particular space but not essentially rooted to it, able to be transferred as circumstances warrant. While Super-8 film or video can also be mobile, the immediacy of the temporal is lost, meaning, the ability to speak or act back to the transmitter during the transmission. These other audio/visual technologies required extra time, a duration that did not match the duration of an event or transmission. [16] This embedding of free radio within the immediate moment enabled a type of proaction/reaction that was not available with the other technologies.

Not that this was an ontological given, however. Guattari realised the contingency of technological development on the activities of state and commercial entities, with the resulting myth that the choices were ‘inevitable’: ‘today one has a tendency to base the legitimacy of this choice on the nature of things, on the “natural” evolution of the technology’ (Guattari 1996 [1979]: 74). This understanding of the ways in which ideologies become a component of technological apparatuses parallels then-concurrent research within film studies regarding the ideological constructs of cinema. The close up, deep focus, techniques that were ‘assumed’ to be inevitable and neutral, were shown to be part of a wider process of signification with historical roots in existing, mainstream ideologies. Jean-Louis Comolli is clear in this respect when he talks about the desire of some film theorists to discover the ‘first’ instance of a particular technique like the closeup:

As soon as one interprets a technical process ‘for its own sake’ (i.e., ‘the first traveling shot in the history of the cinema’) by cutting it off from the signifying practice where it is not just a factor but an effect (i.e., not just a ‘form’ which ‘takes on’ or ‘gives’ a meaning, but itself already a meaning, a signifier activated as a signified on the other scene of film, its outside: history, economy, ideology)—it becomes an ahistorical temporal object. With a few minor adjustments (technical perfecting) it can wander from film to film, always already there and always identical to itself (‘a closeup of the boss and a closeup of the worker are both a closeup’) (Comolli 1986 [1971]: 430).

The ontological flattening of class difference of which Comolli writes is an ideological effect of not only the technical use of similar closeups, but also of film theoretical discourse that collapses the two types of closeups into the same object. Closeup as signifier is always already a signified when we make the assumption of its supposed technological (and thus ideological) neutrality. ‘The technical ideology insists on setting technical practice apart from the systems of meaning, presenting it instead as the cause producing effects of meaning in a film text, and not as itself produced, itself an effect of meaning in the signifying systems, histories, and ideologies which determine it’ (Comolli 1986 [1971]: 432). Along these same lines, Jean-Louis Baudry wrote of the ways that the filmic apparatus, as contemporaneously constructed, erases the productive forces necessary for its creation in order to form the illusion of a complete and continuous subject: ‘The search for such narrative continuity, so difficult to obtain from the material base, can only be explained by an essential ideological stake projected in this point: it is a question of preserving at any cost the synthetic unity of the locus where meaning originates [the subject]—the constituting transcendental function to which narrative continuity points back as its natural secretion’ (Baudry 1974: 44). This ‘narrative continuity’—and therefore the creation of the subject—can only occur insofar ‘that the instrumentation itself be hidden or repressed’ (44).

Thus there are (at least) two ways in which the technological apparatus is not neutral: first, in the suggestion that it could function differently and enable expanded forms of affect; and two, in the ways in which it constructs subjectivity, and the possibility and limitations of that subjectivity as a result of the apparatus. We have already seen this obliquely in the writings of Brecht on radio. Following Brecht, Guattari too requires that free radio provide a two-way communications link that ‘permit[s] the establishment of a veritable feed-back system between the auditors and the broadcast team’ (Guattari 1996 [1979]: 74). Radio can function differently, and by functioning differently it can potentially create more open forms of subjectivity. Free radio therefore needs to be seen less as a means of transmission, and more as a process of (re-)transmission, where the feed-back is not closed upon itself but rather remains open to those normally left out of the corporate- or state-controlled media loop, a loop that is closed to many forms of desire or ‘direct speech’ in Guattari’s words. For Guattari sees this open loop as a means of expressing desire and foregrounding new processes of becoming:

Direct speech, living speech, full of confidence, but also hesitation, contradiction, indeed even absurdity, is charged with desire. And it is always this aspect of desire that spokesmen, commentators, and bureaucrats of every stamp tend to reduce, to filter. The language of official media is patterned on the police languages of the managerial milieu and the university; it all gets back to a fundamental split between saying and doing according to which only those who are masters of a licit speech have the right to act. (Guattari 1996 [1979]: 76)

Free radio would not just be for the rational discussion of issues at hand, but would rather be a space for the unexpected, where, in the case of Italian free radio, ‘very serious debates are directly interrupted by violently contradictory, humorous, or even poetico-delirious interventions’ (75). This is a rejection of the ideologies of mainstream politics, as well as the politics of the traditional left, that require sober contemplation and argumentation that minimizes affective outbursts.

Broadcasting from a kitchen table

Guattari’s comments are imbricated with his relationship with Radio Alice in Bologna, Italy, a pirate radio station that was associated with the autonomism movement in Italy in the late 1970s. [17] Going on the air on February 9th, 1976, Radio Alice came at a time in Italian politics of growing militancy on the left as a result of state oppression in response to protests against the ‘historical compromise’ consisting of the ruling Christian Democrats and the Italian Communist Party, which many on the far left saw as a move designed only to continue the instantiation of neoliberal capitalism and the maintenance of the status quo. [18] Radio Alice existed not only to provide information about events on-the-ground in Bologna through phoned-in comments, but also to explore alternative means of speech, much as its namesake experienced in Lewis Caroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. In the words of the collective behind Radio Alice, Collective A/Traverso, ‘The body, sexuality, the desire to sleep in the morning, the liberation from labor, the possibility to be overwhelmed, to make oneself unproductive and open to tactile, uncodified communication: all this has for centuries been hidden, submerged, denied, unstated’ (Collective A/Traverso 2007: 130). Radio Alice was shut down by the carabinieri on March 12th, 1977 and they subsequently made arrests for ‘delinquency and subversive association’ but were unable to find the station’s founder, Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi (Dosse 2010 [2007]: 288). Bifo had earlier read Guattari’s Psychoanalysis and Transversality and his work with Deleuze, Anti-Oedipus; in fact, both books were key for those involved with Radio Alice (Berardi [Bifo] 2008: 145). Fleeing his arrest warrant in Italy, Bifo made his way to Paris and Guattari’s apartment on rue de Condé. Guattari, whose home was well-known as a safe place for activists to stay, learned of the Italian situation, and specifically Radio Alice, through his hosting of Bifo. When Bifo was arrested by French authorities and put on trial in preparation for extradition to Italy, Guattari formed the Centre d’Initiatives pour de Nouveaux Espaces Libres (CINEL) (Center for Initiatives for New Free Spaces), an organization ‘designed to ensure the defense of prosecuted activists’ (Dosse 2010 [2007]: 290). Also involved in the founding of CINEL were Eric Alliez and Gilles Deleuze. CINEL would also be key in supporting Antonio Negri during his incarceration in Italy starting in 1979 (296–300).

Guattari would write in a preface to the French publication of the works of Collective A/Traverso:

Alice. A radio escape line. A whole engagement of theory—life—praxis—groups—sex— solitude—machine—affection—caressing. No more of the blackmail of ‘scientific’ concepts. […] The people who created Radio Alice would say something like this: it seemed to them that a movement that could succeed in destroying the vast capitalist-bureaucratic machine would, a fortiori, be capable of constructing a new world. Collective competence would grow with collective action; it is not necessary at this stage to be able to produce blueprints for a substitute society (Guattari 1984: 238, 241).

In the words of Michael Goddard, for Guattari, ‘Radio Alice was not an instrument of information but a device for destructuration of the mediatic system aiming for the destructuration of the social nervous system’ (Goddard, n.d.). If Radio Alice had only existed as a means of rational discourse, if it only allowed transmission instead of re-transmission, it could only have consisted in maintaining the ideology of passive reception and the acceptance of existing structures. What interested Guattari in Radio Alice instead was its opening for the ‘destructuration’ of the social order, and the possibility that it could be re-created or performed, live, in a temporality of its own participants’ choosing, and for purposes of experimentation and becoming rather than ingestion and acceptance.

Free radio in France faced state repression as well, but not to the extent experienced in Italy. Nevertheless, via transmitters smuggled in from Italy, Guattari helped found Radio Tomato with other CINEL activists in 1980, with early broadcasts originating from his kitchen table (Dosse 2010 [2007]: 304). Radio Tomato broadcast news programs and cultural programming, as well as debates on events in Poland, Lebanon, Israel, and Palestine. [19] In his monumental account of the individual and joint work of Deleuze and Guattari, François Dosse writes that, ‘This airwave experiment corresponds to a practical extension of Deleuze and Guattari’s ideas. It is a model of a transversal rhizomatic system that breaks with State- and market-based vertical logics’ (Dosse 2010 [2007]: 304).

Scanning the Satellite Airwaves

What is apparent from the preceding discussion is desire manifested in exploring the fringes of particular technological configurations. Rather than taking what was given, free radio supporters, following Brecht, set to recreate the telematic by implementing what was possible-but-not-yet-existing. By actualising these models, free radio practitioners constructed new spaces for the expression of affect, at the same time critiquing the structure of the existing ideological apparatuses. Similarly, those with satellite signal receivers in the 1980s and 1990s were able, if suitably interested, to capture feeds that existed in the proverbial aether but were not meant for public consumption. At this time satellite signals were sent unencrypted, meaning that they could be watched and captured by anybody with the right tools. These signals also consisted of excesses that were not normally seen within the confines of standard television programs: off-the-cuff comments of interviewees, the repetition of subtly different interviews to geographically disparate locations, the creation of on-air personalities through the actions of handlers. The American documentary filmmaker Brian Springer gathered hundreds of hours of these sorts of feeds for his documentary Spin (Springer 1995). Drawing from material in the turbulent year of 1992, with the American presidential election, Los Angeles riots, fights over reproductive rights, and the 500th ‘anniversary’ of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the ‘new world’, Spin shows the satellite feed in its ‘raw’ form, prior to its manipulation and splicing for the purposes of broadcast. The technological apparatus is laid bare through the capture of and re-presentation of the feed. Gone are the mixing tables, the teams of editors and producers that take the ‘raw’ audio/visual feed and turn it into something for consumption. The film theorist Patricia Zimmerman has written with respect to Spin that, ‘In these feeds, the performative mode of television, which packages news and sanitizes private discourse, recedes. Spin crawls between the interstices of television, the space of live, nonstop satellite hookups in between national and international broadcasts, in effect, working the seams rather than the programs’ (Zimmerman 2000: 175). The borderlands come to the fore, challenging a media culture where images are transformed within closed editing booths and then re-transmitted to an absorbing public with no possibility of meaningful response.

Similarly to Spinger’s work, the activities of the Slovene artist Marko Peljhan and his Makrolab (Zavod Projekt Atol 2003) project opens up a space for critiquing the control of wireless spectra by corporate, state, and military entities. Makrolab exists as an autonomous structure of Space-Age design, a silver-clad angular cylinder meant to evoke at once the heralding of a clean future as well as the fear of atomic annihilation and the subsequent need for hardened shelters. Within Makrolab are a series of workspaces meant to provide visitors (other artists, scientists, or exhibition guests) with the ability to ‘scan’ the space of telecommunications signals. Much as with Spin, the idea is to work at the borders of legality, examining wireless transmissions that are not meant for public perusal. [20] In the words of choreographer and media theorist Johannes Birringer, Makrolab ‘can gather information about valuable data concerning security, the environment, weather, health, economic and financial transactions, political conflicts, and scientific research. In doing the kind of observation and analysis generally conducted by institutional, private, and state monopolies, Makrolab takes on a counter-position, a heterotopic praxis of “information gathering” that extracts valuable data from supra-individual, corporate, and transterritorial networks’ (Birringer 1998: 71). Makrolab becomes a testing ground for developing novel relationships to the telematic spectrum, relationships that are formed out of self- or group-interest rather than because of the market: ‘Tinkering with the toolbox of net technologies and opening alternative channels of interaction and exchange (the “gift economy” of net activists), such tactical initiatives imply economic analysis of corporate logistics on one hand, and new forms of self-organisation, group-ware channeling, and non-profit models of decentralised public-access connectivity on the other’ (73). Brian Holmes further connects Makrolab with Peljhan’s own upbringing within a Slovenia that quickly went from a member of the Republic of Yugoslavia to a nation entering the neoliberal milieux, a change that resonates in certain ways with Spain’s own movement from fascist dictatorship to capitalist democracy fifteen years earlier: ‘…within a device that encapsulates certain aspects of the Slovene experience, fragmented images from a wider variety of vanguard projects can knit together into complex sensorial refrains, interrupting the normalised modulation of time imposed by the commercial and military cultures of transnational capitalism, and loosening up subjectivity for original work with the most challenging scientific and symbolic material, at variance with the dominant patterns’ (Holmes 2007).

But lest I give the impression that tinkering with the ‘raw’ feed is the only means by which new subjectivities are formed, I want to consider another example. In a different context the ‘sanitized’ feeds themselves—indeed those that are constructed by media networks and received by a willing public—can become a means of emancipation, according to the Moroccan feminist and sociologist Fatema Mernissi. According to her ethnographic research, the wide availability of satellite dishes in Morocco has enabled a certain type of ‘conversation’ to take place regarding the role of women in society due to the presence of female hosts on channels such as al-Jazeera discussing such topics as ‘sexual inadequacy’. The ability for the satellite signal to reach into every home made this a communal experience in ways that the Internet currently does not provide: ‘[satellite broadcasting] creates the highly political public space where the entire community is gathered to debate vital issues. By contrast, the internet, which is basically more of an individual experience, does not have that theatrical public dimension, so central to Islam, where the sexes are not supposed to have the same access and the same behavior’ (Mernissi 2004: section 3). Because of the ubiquity of satellite dishes, and the signal’s omnipresence in the air, experiences and conversations can be had between the sexes that are not possible in other types of spaces. This has proven controversial for the traditional notion of the umma, or Muslim community, that forms the fabric of Islamic society. The ubiquity of satellite television has forced changes to the structure of the umma, precisely because of the technological reach of its wireless feed. [21]

Returning to the data feed

How do the discussions of pirate radio and the satellite feed relate to the work of hackitectura at the fadaiat event? The live wireless data transmission that linked Tarifa and Tangier is a reconfiguration of the concept of feed from both pirate radio and satellite television. On the one hand, the fadaiat feed could be watched passively by electronic visitors to the website during the event. The feed would appear to them as nothing more than a standard presentation of any other ‘live’ event. Visitors from various locations around the world could view the event even if they could not be physically co-present. On the other hand, people could involve themselves in the feed via a process of re-transmission. Neither Tarifa nor Tangier was more of a ‘prime’ node than the other, meaning that transmissions (or re-transmissions) could occur from either location. GISS enabled the streaming of experiences in both directions, in full duplex. Rather than talking amongst each other in front of a screen obstinate to any form of interaction, fadaiat participants could re-act ‘in real-time’ to what was taking place on the other side. In light of the geopolitical relationship between Spain and Morocco (their intertwined histories, their positions on the continents of Europe and Africa, their uneasy relationship to the presence of Great Britain at their backdoor) this opening of possibilities should not be underestimated. While live links between two geographically separate locations had occurred for artistic purposes in the past (most notably with Hole in Space (1980) by Kit Galloway and Sherry Rabinowitz), the fact that the link used for fadaiat was created by the participants themselves needs to be noted. Control of the feed remained with the organizers of fadaiat , meaning that content decisions remained solely in their hands. No-one could tell them to cut the feed; no-one could force them to switch to another camera. The control of the infrastructure and the technological apparatus gave them control over what could be said—and gave them the opportunity to give up content control altogether.

So this was not just a performance of televisual liveness, as Jane Feuer argues in her well-known essay (Feuer 1983); events are not being constructed temporally-prior in order to make it appear as if the event were happening live. Yet the participants in fadaiat would appear to be under no false pretences that their own live event is somehow ontologically prior or pure: the representations are, in a certain sense, mediatised in similar fashions to those of corporate or state media. The frame remains the same shape (albeit somewhat smaller than normal because of limitations on network bandwidth) and cameras are still placed in relatively standard positions. Nevertheless, authority remains in their hands; control of who and what gets shown, where and when the images appear, and, most importantly, why the event takes place remains local. Participants wrest power over self- and collective-determination from the authorities. The participants in fadaiat thus move in a different space than mere critique of dominant ideologies. The creation of the wireless link is itself both a comment on the regulation and control over the telematic spectrum and a means of performing an alternative configuration of these technologies, a configuration that foregrounds the desire of individuals and collectives to decide upon their own forms of discourse and their own means of representation.

Ethico-political subjectivity across the straits

I want to finish by tying the work of hackitectura in the fadaiat project to wider concerns about the formation of subjectivity within an ethico-political domain. This discussion draws heavily from the theoretical accounts of Guattari in Chaosmosis, his last published book and one in which the technological plays an important role. His examination of the production of ‘minority becomings’ via new processes of subjectivity, partially constructed by technology, came to the fore in Chaosmosis. Important for my discussion of fadaiat is Guattari’s insistence on including the technological in any discussion of a post-media ecosophy. Counter to certain strands of thought that would see in (presumably modern) technology only the forces of domination and capitalist control, Guattari suggests that ‘Technological developments together with social experimentation in these new domains are perhaps capable of leading us out of the current period of oppression and into a post-media era characterised by the reappropriation and resingularisation of the use of media’ (Guattari 1995: 5), making specific reference to the potential for ‘interactivity between participants’ (6) and thus suggesting a potential link between these new technologies and his earlier comments about free radio.

Guattari is careful to distance his approach from one that would posit a transcendental, universal Subject that exists prior to modes of signification. Subjectivity, therefore, is not meant to create a Subject in the image of something that already exists. Yet this distaste for the universal Subject does not mean that we should turn to ‘conservative reterritorializations of subjectivity’ (Guattari 1995: 3) that make calls for actualizing what is already known but not presently existing (ethnic groupings, certain types of identity politics), that would ultimately reflect previous forms of subjectivity only in the guise of seemingly new subjects. Nor is the formation of subjectivity based on linguistic signification alone. Guattari is as interested in non- or pre-discursive modes as he is in speech. He is wary of how both Capital and the ‘conservative reterritorializations’ can lead to retrograde movements of subjectivity: ‘Subjectivity is standardised through a communication which evacuates as much as possible trans-semiotic and amodal enunciative compositions’ (104). By focusing on only one modality for subjectivity we would close ourselves off from alternative ‘enunciative compositions’ that create subjective reconfigurations hitherto unknown. It is within the potential of the ‘trans-semiotic and amodal’ virtual that we can conceive of and perform different forms of living. This is key for my consideration of free radio and the work of the fadaiat project. Nowhere within fadaiat was there a limitation of the project to only the linguistic, only the rational presentation of facts and accounts. Rather, in addition to this was the expression of affect, the playful, the non-rational as molecular components of an increasing sum, individual elements yet part of a whole that we can speak of as fadaiat.

There is here a certain generative productivity at work that is lost within traditional accounts of technological use. Within this discourse the technological is seen as a means to an end, a mere tool for the completion of some task. Yet the economy in the fadaiat project—within its social-technical assemblage—produces a different type of efficiency, an efficiency towards the subjective via its representational and performative aspects. The specific social and technical configurations open opportunities for reaching certain types of enunciations that would be impossible within traditional arrangements of rational social and technical systems. In talking about the power of poetic discursivities, Guattari writes that, ‘Its efficiency lies in its capacity to promote active, processual ruptures within semiotically structured, significational and denotative networks, where it will put emergent subjectivity to work’ (19; my emphasis). This type of efficiency is not that of a rational politics, nor of a belief in the telos of a given technology; signification is too intransigent for these techniques. Rather, poetic discursivities provide a more direct way to cut through the power of existing semiotic networks via an ‘ethico-aesthetic paradigm’ (to use the subtitle of Chaosmosis) that, partially because of its bastard status as a strategy, can create the ‘ruptures’ needed for the expression of something novel. [22]

Consensus politics this is not, and it intertwines with Guattari’s own political experiences with Bifo and Radio Alice in Bologna, among many other activities. Specifically, the Italian left experienced in the 1970s the ways in which Parties could turn on their members, most notably in the coalition government of the Christian Democrats and the Communist Party, a coalition designed to hold the status quo in a barely-stable state. According to Michael Goddard, ‘what is behind this polarisation [of the Italian left] was the emergence of a new regime of consensus or control in which all previously existing forms of resistance such as trade unions or the communist party would be tolerated provided they fit into the overall regime of consensual control, for which they provide very useful tools for subjective reterritorialisation’ (Goddard, n.d.). Suggesting or embodying alternatives to the allowed institutions (such as what Radio Alice did) resulted in massive state repression. Nevertheless, the members of Radio Alice, along with Guattari’s CINEL colleagues, worked to create alternative networks of people and collectives that expressed new means of working against injustice and towards a different present-future. With fadaiat, we see one actualization of this: by creating their own network infrastructure, by spreading their work via libre software and a freely downloadable book, by building networks of solidarity with both local groups and more geographically-dispersed organizations, hackitectura and the members of the fadaiat project are engaged in the marshalling the ‘trans-’ of which Guattari writes. Trans-semiotic, trans-border, trans-media. Consensus works on the assimilation of everything into the ‘intra-’, while agonism or non-consensus requires an affirmation of the ‘trans-’. This does not rule out a collective politics; rather, collectivity can be understood as beyond and before the individual (Guattari 1995: 9) and thus respectful of both individuals’ and collectives’ abilities to self-determine their own subjectivity absent the force of an unifying institution.

Subjectivity in this sense is not naively utopic, for it does not deny the power of trans-national capitalism and neoliberal economic policies, nor does it require a tabla rasa. What it does deny is a purely rational response that rules out the subjective force of individuals and groups. And it denies that this form of subjectivity should only be a response, a post-hoc action that takes as given the pre-existing, the past. Rather, it is productive in a way that is temporally oriented towards the present-future, with the knowledge that such words as ‘present’ and ‘future’ should not be seen as bounded terms but rather refer to multiple overlapping temporalities of duration that, put together, articulate potential spaces of action and creation. It is a movement away from, in the words of Goddard, the ‘deadening of relationality, affect and desire in the direction of pure functionality and aggressivity’ (Goddard, n.d.). Performance of subjectivity like that observed in fadaiat is rather a repudiation of the ideology of functionality and a discarding of an unwavering belief in institutional politics. Fadaiat suggested a different type of ethics, one that draws on the capacity of people to create and come together under their own volition. ‘There is an ethical choice in favour of the richness of the possible, an ethics and politics of the virtual that decorporealises and deterritorialises contingency, linear causality and the pressure of circumstances and significations which besiege us’ (Guattari 1995: 29). With fadaiat and the work of hackitectura we see a strong argument against the status quo and the call for a new way of approaching not only immigration, but also ethico-political action as a whole. Aspects of the virtual become actualized creating molecular revolutions that, combined across a multitude of temporalities, generates a reconfigured world founded on mediated relationships that bring lived experience to the fore. The temporary autonomous zone of fadaiat —a zone that refracts not only the pirate enclaves of old, but also the free-trade zones of the Kingdom of Spain—is a micro-revolution in and of itself, a series of points within a growing multitude of temporal events that, en masse, form a counter to the power of neoliberal globalization and a manifestation of a new potential state of the world. [23]

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback and to Zita Joyce for her careful reading of the article. Thanks also to Phoebe Sengers and Amy Villarejo for comments on earlier drafts. Finally, my gratitude to Claudia Pederson for not only her commentary but also her support throughout the writing of this paper.

Biographical Note

Nicholas Knouf is a PhD candidate in Information Science and Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Graduate Fellow at the Society for the Humanities at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. His research explores the interstitial spaces between information science, critical theory, digital art, and science and technology studies. He is also a media artist, producing works that, among other things, question the academic publishing industry, suggest new forms of communication via mobile phones, and provide spaces for the exploration of new vocal relationships with robotic creatures. More information can be found at his website, https://zeitkunst.org.

Notes

- [1] The word fadaiat is an Arabic word meaning ‘spatial objects’ or ‘through spaces’ and is often used to refer to satellites as well as space ships. See Monsell Prado and de Soto Suárez (2006: 219).

- [2] While my references to pirate radio will primarily come from the late 1970s and early 1980s, I do not want to ignore the plethora of pirate radio stations that remain broadcasting throughout the world, flittering in and out of existence as circumstances allow.

- [3] hackitectura dissolved in early 2011 after existing for a decade.

- [4] Key texts outlining the theory and practice of hacktivism in the sense of electronic civil disobedience can be found in Critical Art Ensemble (1994, 1996). Such practices can also be related to the history of a more narrow form of hacking within computer culture, hearkening back to the days of phone phreaking. For one of the most well-known statements see The Mentor (1986). Such practices have one contemporary manifestation within the activities of Anonymous or LulzSec; for an anthropological take on their actions see Coleman (2011).

- [5] Free/libre/open source software (FLOSS) refers to the development and release of software tools along with the human-readable source code, meaning the text of the computer instructions that can be understood by a programmer or hardware designer, rather than the binary machine code alone that can only be run by the computer and not easily understood by a human. Free software advocates consider this a fundamental freedom of computing, suggesting that all should have the ability to know how programs are written. This is in contrast to commercial development of software, where the source code is often considered a trade secret or proprietary intellectual property. Debates regarding this spectrum have occurred throughout the history of digital computing with FLOSS becoming more and more prominent over the past decade. Free software is customarily developed in a collective, decentralized fashion with programmers collaborating in a geographically-dispersed manner. For recent anthropological accounts of the development of FLOSS see Coleman (2004); Coleman and Golub (2008); Kelty (2008). hackitectura specifically align themselves with the free/libre side of FLOSS, which stresses the ability to share and distribute computing knowledge, rather than the open source side, which in contrast stresses the economic benefits of efficiency that come with having the source code available.

- [6] Important to note here is that this libre software does not merely replicate in a mimetic fashion the capabilities of existing commercial products; rather, it contains potentials and capabilities that would not be possible if the whims of the market or stockholders were the final arbiters.

- [7] Indymedia began as a means of reporting on the protests at the 1999 WTO meeting in Seattle, Washington, USA, where activists created an online platform for the spread of tactical information, news, and commentary that bypassed mainstream corporate media sources. Indymedia sites are well known for allowing anyone to post information on their ‘news-wire’, an important tool that is widely used by protesters during fast-moving events. Since then, Indymedia has expanded to over a hundred ‘nodes’ around the world, with each node governed independently and presented using whatever local language(s) is/are necessary. Indymedia thus exists as an assemblage of material relationships consisting of geographically-specific collectives, as well as a software platform that enables a form of ‘citizen journalism’ via technologies such as the mobile phone and the Internet. There are additionally Indymedia nodes that focus on audio via online and terrestrial radio (https://radio.indymedia.org/), linking Indymedia to a longer history of pirate and participatory radio. For more on the history of Indymedia see Juris (2008: 267–286) and Milberry (2003, 2009), and for its software development see Hill (2003).

- [8] It is important to recall that the word ‘network’ has as its first definition one that highlights qualities of materiality, corporeality, and the production of textiles. See Oxford English Dictionary (2012).

- [9] Workshop notes prior to this event discuss ‘mapping games’, potential connections with local organisations in Morocco, as well as a band that could perform during the event; see chaser (2005).

- [10] See, for example, Galloway (2004); Galloway and Thacker (2007); Terranova (2000).

- [11] Yet it is easy to understand if we consider the cybernetic practice of ‘black-boxing’, where complicated systems can be reduced to simple relationships of inputs and outputs, and where other factors are abstracted into the background. Research in science and technology studies have worked extensively to ‘open’ the black box of the creation of facts and artifacts in order to counter Whig histories of development. See, for example, Pinch and Bijker (1984); Winner (1986); Latour (1987); Winner (1993); Nieusma (2004).

- [12] This is due to the need for ‘line-of-sight’ access, meaning that one side needs to be able to ‘see’ the other side via a straight imaginary line. Thus, any movement of either installation (due to high winds) could potentially knock out the signal.

- [13] For an account see Klein (2000: 311–324). Pirate radio was also key to the spread of dance music beginning in the 1990s; for a contemporaneous description of pirate radio in the UK see Fuller (2005: 13–53).

- [14] For more on the development of radio in America, and especially the role of amateur transmitters and their relationships with corporate and state entities, see Douglas (1987); for the particular case of the American Radio Relay League, see David (2008: 136–190). Radio and its pirates developed differently in other countries in Europe; for a history of these relationships in Great Britain see Johns (2011). In Japan Tetsuo Kogawa has been instrumental in the development of a ‘micro-FM’ movement that takes advantages of both legal loopholes and the density of living within Tokyo; see Kogawa (1990, 2003).

- [15] Guattari unfortunately ignores the importance of the Sony Portapak technology to feminist artists throughout the world and in France specifically; see Jeanjean (2011).

- [16] While live television existed, it required access to the ‘big industrial enterprise’ that Guattari decried.

- [17] As François Dosse notes, Guattari’s family had roots in Bologna; how much of this can be said to have affected Guattari’s connection with Italian activism is unclear. See Dosse ( 2010 [2007]: 22).

- [18] For much more on the development of autonomism in Italy in the 1970s see Wright (2002).

- [19] See Michael Goddard’s recent article (2011) in Fibreculture for more on Guattari’s experiments with radio in France.

- [20] Indeed, at its unveiling during Documenta X in 1997, Brian Springer was present as an on-site consultant.

- [21] For examples of this reconstitution of publics within the context of blogging in Egypt and Tunisia, see Otterman (2007) and Elian (2011).

- [22] For a similar argument on the need for progressive activists to understand the power of affect and fantasy, see Duncombe (2007).

- [23] To end by joint references to temporary autonomous zones and pirate enclaves is to recall the importance of the Madiaq region (and the Mediterranean in general) to Peter Lamborn Wilson’s notion of ‘pirate utopias’ and specifically the Republic of Salé on the Atlantic coast of north Africa, not far away from the Straits of Gibraltar (Wilson 1995). Such historically-existing enclaves were key for the development of the temporary autonomous zone concept as mediated by Wilson’s moniker Hakim Bey (Bey 1991). All this is to further note the importance of reactivating older temporalities in the present as necessary.

References

- Al-Jwarizmi Contributors. ‘Al-Jwarizmi’, (2005), https://hackitectura.net/aljwarizmi/.

- Baudry, Jean-Louis. ‘Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus’, trans. Alan Williams. Film Quarterly 28.2 (1974): 39–47, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1211632.

- Berardi (Bifo), Franco. Felix Guattari: Thought, Friendship, and Visionary Cartography, trans. Giuseppina Mecchia and Charles J. Stivale. (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

- Bey, Hakim. T.A.Z. the Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism. (Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 1991).

- Birringer, Johannes. ‘Makrolab: A Heterotopia’. PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art Journal 20.3 (1998): 66–75.

- Brecht, Bertolt. Brecht on Theatre. (New York: Hill / Wang, 1964).

- chaser. ‘dash fadaiat tarifa ljubljana workshop notes’, 22 March (2005), https://mcs.hackitectura.net/tiki-index.php?page=dash%20fadaiat%20tarifa%20ljubljana%20workshop%20notes.

- Coleman, E. Gabriella. ‘Anonymous: From the Lulz to Collective Action’, 6 April (2011), https://mediacommons.futureofthebook.org/tne/pieces/anonymous-lulz-collective-action.

- Coleman, E. Gabriella, and Alex Golub. ‘Hacker practice: Moral genres and the cultural articulation of liberalism’. Anthropological Theory 8.3 (2008): 255–277.

- Coleman, Gabriella. ‘The Political Agnosticism of Free and Open Source Software and the Inadvertent Politics of Contrast.’ Anthropological Quarterly 77.3 (2004): 507–519.

- Collective A/Traverso. ‘Radio Alice—Free Radio’, in Autonomia: Post-Political Politics, eds. Sylvere Lotringer and Christian Marazzi (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2007), 130–135.

- Comolli, Jean-Louis. ‘Technique and Ideology: Camera, Perspective, Depth of Field [Parts 3 and 4]’, in Philip Rosen (ed.), trans. Diana Matias, Narrative, apparatus, ideology: a film theory reader. Revisions in translation by Marcia Butzel and Philip Rosen. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986; 1971), 421–443.

- Critical Art Ensemble. The Electronic Disturbance. (New York: Autonomedia, 1994), https://www.critical-art.net/books/ted/.

- Critical Art Ensemble. Electronic Civil Disobedience: and Other Unpopular Ideas. (New York: Autonomedia, 1996), https://www.critical-art.net/books/ecd/.

- David, Shay. ‘Open Systems in Practice and Theory: The Social Construction of Participatory Information Networks’. PhD diss., Cornell University (2008).

- de Soto Suárez, Pablo. ‘Reunion 03’, 1 January (2005), https://mcs.hackitectura.net/tiki-index.php?page=Reunion+03.

- Degoyon, Yves. ‘About Giss by Yves Degoyon 2007’, (2007), https://giss.tv/wiki/index.php/About_Giss_by_Yves_Degoyon_2007.

- Dosse, François. Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari: Intersecting Lives, trans.

- Deborah Glassman. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010; 2007).

- Douglas, Susan J. Inventing American Broadcasting, 1899–1922. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987).

- Duncombe, Stephen. Dream: Re-Imagining Progressive Politics in an Age of Fantasy. (New York: The New Press, 2007).

- Elian, May. ‘Talking with award-winning blogger “Tunisian Girl”’, 19 April (2011), https://ijnet.org/stories/talking-award-winning-blogger-tunisian-girl.

- Feuer, Jane. ‘The Concept of Live Television: Ontology as Ideology’, in E. Ann Kaplan (ed.), Regarding Television: Critical Approaches—An Anthology. (Los Angeles: American Film Institute, 1983), 12–22.

- Fuller, Matthew. Media Ecologies: Materialist Energies in Art and Techniculture. (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2005).

- Galloway, Alexander R. Protocol. (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2004).

- Galloway, Alexander R., and Eugene Thacker. The Exploit: A Theory of Networks. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007).

- GISS Contributors. ‘Global Independent Stream Support (GISS)’, (2008), https://giss.tv/.

- Goddard, Michael. ‘Towards an Archaeology of Media Ecologies: ‘Media Ecology’, Political Subjectivation and Free Radios’. Fibreculture 17 (2011): 6–17.

- Goddard, Michael. ‘Felix and Alice in Wonderland: The Encounter between Guattari and Berardi and the Post-Media Era’, (n.d.), https://www.generation-online.org/p/fpbifo1.htm.

- Goebbels, Joseph. ‘The Radio as the Eight Great Power’, (1999), https://www.calvin.edu/academic/cas/gpa/goeb56.htm.

- Guattari, Félix. ‘Millions and Millions of Potential Alices’, in trans. Rosemary Sheed, Molecular Revolution: Psychiatry and Politics. (New York: Penguin Books, 1984), 236–241.

- Guattari, Félix. Chaosmosis, trans. Paul Bains and Julian Perfanis. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995).

- Guattari, Félix. ‘Popular Free Radio’, in Sylverè Lotringer (ed.), trans. David L. Sweet, Soft Subversions. (New York: Semiotext(e), 1996; 1979), 73–78.

- Guattari, Félix. The Three Ecologies, trans. Ian Pindar and Paul Sutton. (New York: Continuum, 2008).

- hackitectura.net. ‘hackitectura digital workspace: TIMECODE’, (2011), https://mcs.hackitectura.net.

- Harris, Mike, and Dave Gough. ‘Fadaiat: Full List of Contributors’, (2004), https://flakey.info/fadaiat/colaboradores.xhtml.

- Harris, Mike, and Dave Gough. ‘Fadaiat: Wireless 802.11b link across the Strait of Gibraltar for no-border media labour’, (2004), https://flakey.info/fadaiat/.

- Hill, Benjamin Mako. ‘Software (,) Politics and Indymedia’, (2003), https://mako.cc/writing/mute-indymedia_software.html.

- Holmes, Brian. ‘Coded Utopia: Makrolab, or the art of transition’, (27th March 2007), httpss://brianholmes.wordpress.com/2007/03/27/coded-utopia/.

- Indymedia Estrecho/Madiaq. ‘Indymedia Estrecho/Madiaq’, (2011), https://estrecho.indymedia.org/.

- Jeanjean, Stéphanie. ‘Disobedient Video in France in the 1970s: Video Production by Women’s Collectives’. Afterall 27 (2011): 5–13.

- Johns, Adrian. Death of a Pirate: British Radio and the Making of the Information Age. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2011).

- Juris, Jeffrey S. Networking Futures: The Movements Against Corporate Globalization. (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2008).

- Kelty, Christopher M. Two Bits: The Cultural Significance of Free Software. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008).

- Klein, Naomi. No Logo: No Choice, No Space, No Jobs. (New York: Picador, 2000).

- Kogawa, Tetsuo. ‘Toward Polymorphous Radio’, (1990), https://anarchy.translocal.jp/non-japanese/radiorethink.html.

- Kogawa, Tetsuo. ‘From Mini FM to Polymorphous Radio’, in Joanne Richardson (ed.), Anarchitexts: Voices from the Global Digital Resistance. (Brooklyn, NY, USA: Autonomedia, 2003), 177–182.

- Latour, Bruno. Science in Action: How to follow scientists and engineers through society. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1987).

- Leys, Ruth. ‘The Turn to Affect: A Critique’. Critical Inquiry 37.3 (2011): 434–472.

- Maleno, Helna. ‘border citizenship’. In Monsell Prado and de Soto Suárez 2006: 187–192.

- Mazzarella, William. ‘Affect: What is it Good for?’, in Saurabh Dube (ed.), Enchantments of Modernity: Empire, Nation, and Globalization. (London, New York, and New Dehli: Routledge, 2009), 291–309.

- Mernissi, Fatema. ‘The Satellite, the Prince, and Scheherazade: The Rise of Women as Communicators in Digital Islam’. Transnational Broadcasting Studies 12 (2004): n.p. https://www.tbsjournal.com/Archives/Spring04/mernissi.htm.

- Mezzadra, Sandro. ‘borders/confines, migrations, citizenship’. In Monsell Prado and de Soto Suárez 2006: 175–180.

- Milberry, Kate. ‘Indymedia as a Social Movement?’ Master’s thesis, University of Windsor (2003).

- Milberry, Kate. ‘Geeks and Global Justice: Another (Cyber)World is Possible’. PhD diss., Simon Fraser University (2009).

- Monsell Prado, Pilar, and Pablo de Soto Suárez, eds. Fadaiat: libertad de movimiento + libertad de conocimiento. (imagraf impresores, 2006), https://fadaiat.net/english.html.

- Nieusma, Dean. ‘Alternative Design Scholarship: Working Toward Appropriate Design.’ Design Issues 20.3 (2004): 13–24.

- Otterman, Sharon. ‘Publicizing the private: Egyptian women bloggers speak out’, (2007), https://www.arabmediasociety.com/?article=13.

- Oxford English Dictionary. ‘network, n. and adj.’, (2012), https://oed.com/view/Entry/126342.

- Pérez de Lama, José. ‘Public Space and Electronic Flows: Some Experiences by hackitectura.net’, in, Inclusiva-net #2: Digital Networks and Physical Space. Texts of the 2nd Inclusiva-net Platform Meeting. (Madrid: Área de Las Artes., 2009), 99–106.

- Pérez de Lama, José, Pablo de Soto Suárez and Sergio Moreno. ‘FADAIAT: Through spaces at Fortress EU’s southwest border.’, 7 March (2005), https://mcs.hackitectura.net/tiki-index.php?page=txt_AcousticSpace.

- Pinch, Trevor J., and Wiebe E. Bijker. ‘The Social Construction of Facts and Artefacts: Or How the Sociology of Science and the Sociology of Technology Might Benefit Each Other’. Social Studies of Science 14.3: (1984): 399–441. https://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0306-3127%28198408%2914%3A3%3C399%3ATSCOFA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-N.

- Pullens, Roy. ‘migration management: exporting the IOM model in the name of EU security’. In Monsell Prado and de Soto Suárez 2006: 181–185.

- Schneider, Florian. ‘fadaiat//borderline academy’, 22 May (2005), https://www.mail-archive.com/nettime-l@bbs.thing.net/msg02740.html.

- Springer, Brian. 1995. Spin. Film, https://www.emoore.org/spin/.

- Terranova, Tiziana. ‘Free Labor: Producing Culture for the Digital Economy’. Social Text 18.2 (2000): 33–58.

- The Mentor. ‘The Conscience of a Hacker’, 8 January (1986), https://www.phrack.org/issues.html?issue=7&id=3&mode=txt.

- Toret, Javier, and Nicolás Sguiglia. ‘mapmaking excess. labour and frontier by the movement’s paths’. In Monsell Prado and de Soto Suárez 2006: 193–199.

- Wilson, Peter Lamborn. Pirate Utopias: Moorish Corsairs & European Renegadoes. (Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 1995).

- Winner, Langdon. ‘Do Artifacts Have Politics?’, in, The Whale and the Reactor: A Search for Limits in an Age of High Technology. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 19–39.

- Winner, Langdon. ‘Upon Opening the Black Box and Finding It Empty: Social Constructivism and the Philosophy of Technology’. Science, Technology, & Human Values 18.3 (1993): 362–378.

- Wright, Steve. Storming Heaven: Class Composition and Struggle in Italian Autonomist Marxism. (Sterling, VA: Pluto Press, 2002).

- Zavod Projekt Atol. ‘Makrolab’, 12 December (2003), https://makrolab.ljudmila.org/.

- Zimmerman, Patricia R. States of Emergency: Documentaries, Wars, Democracies. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000).